Friction Dynamics Model: Design for Traction

Two tempos, one promise Link to heading

We got good at making things smooth. Tap to buy. Swipe to share. Done. Sometimes that’s perfect. Reordering coffee beans shouldn’t feel like a committee meeting. But not everything deserves a slide. A first‑time, high‑ticket purchase with no returns should breathe differently than a routine refill. A small hold beside “Buy”, a two‑line explainer, a visible way to cancel within 24 hours. The tempo changes and the action feels more chosen.

The same goes for speech. You’re about to reshare an article you haven’t opened. A thin seam appears: “Read first?” with a short preview. Twitter tested this in 2020 and found that more people opened the link before sharing, and knee‑jerk resharing dropped 22 . The delay is a few seconds, yet the post you make feels more owned.

That’s the promise of two tempos: fast for routine, serious when it’s serious. The surface won’t slow everything. Only the moments where a pause buys you better judgment. But why do pauses and interruptions sometimes feel right and sometimes irritating?

This builds on what psychologists call desirable difficulty, the principle that the right kind of resistance actually improves outcomes 1 . When Robert and Elizabeth Bjork studied learning and memory, they found that introducing strategic difficulty (spacing out practice, varying contexts, forcing retrieval) led to better long‑term retention even though it felt harder in the moment. The key word here is desirable. The difficulty has to serve learning or judgment, not just add friction for its own sake. In interface terms: a pause before an irreversible purchase can improve decision quality. A needless CAPTCHA before viewing your own photos is just punishment.

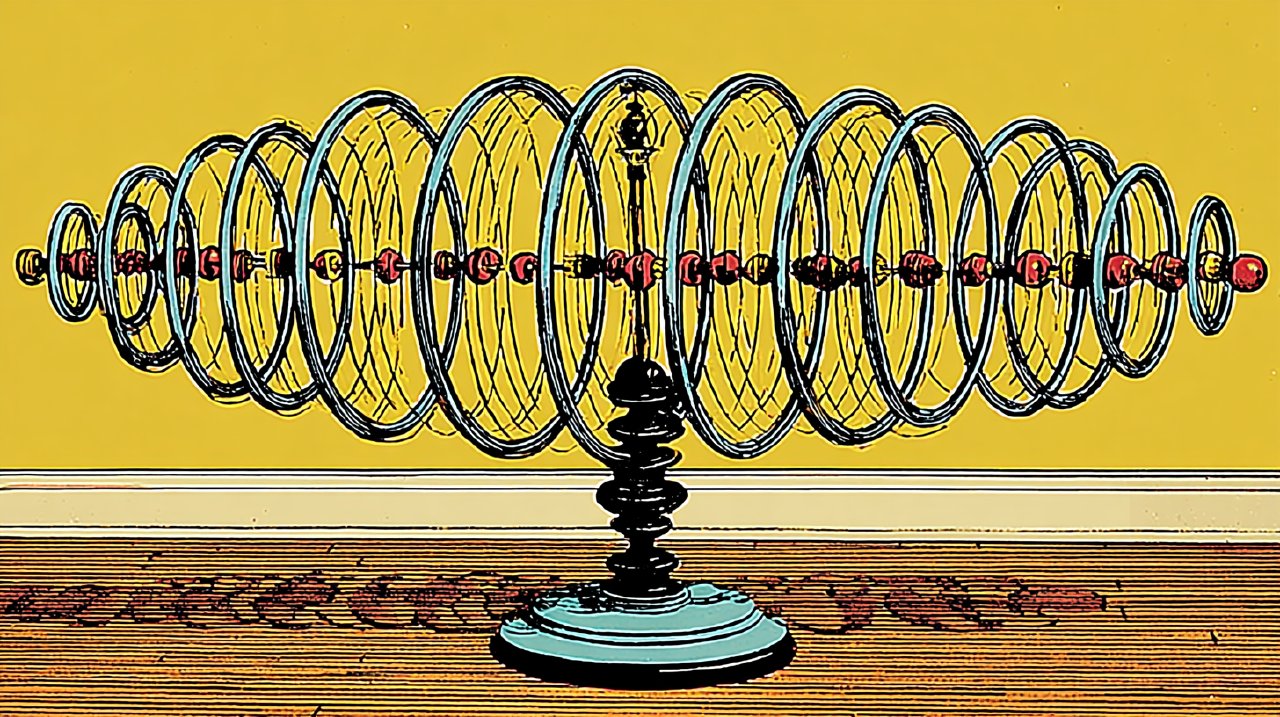

The Friction Dynamics Model Link to heading

The Friction Dynamics Model (FDM) is a framework for deciding what should change when. It works by identifying seams, natural transition points where momentum resets. After you type, when you submit, before a post goes wide, after you add to cart. At those seams, the model evaluates three dimensions:

Uncertainty (system): How confident is the system right now? Is the AI matching similar names with 60% confidence or 98%? Is fraud detection firing on strong signals or weak hunches?

Novelty (person): Is this new for this person in this situation? First time buying this category? First time posting to this audience size? First time filing this type of claim?

Reversibility (action): How hard is this to undo? Can you unsend in 10 seconds, cancel in 24 hours, or is this permanent the moment you click?

When all three dials are quiet (high confidence, familiar territory, easy to undo), the interface stays out of the way. When they spike, the register shifts. A short rationale appears, the ask gets specific (one edit tip, one alternate lens), and a clear path to undo or appeal comes into view. No sermon. Just a different pace that fits the moment.

Underneath sits a simple ethic: match pace to stakes. Use friction as orientation, not punishment.

Why this matters now Link to heading

“Frictionless” once sounded like unambiguous progress. Then AI made it cheap to shape many surfaces (tempo, tone, path) on demand. If the interface can adapt in real time, the question isn’t “how do we remove friction?” but “what should change when, and for whose good?”

Two concepts help us navigate this. Stewart Brand’s pace layers remind us that systems operate at different speeds. Fashion moves fast, infrastructure moves slowly, and trust lives in the coupling between them 18 . A payment system needs fast transactions sitting on top of slow, stable security protocols. When we collapse everything to one speed (instant gratification all the way down), we sacrifice the slower rhythms that enable reflection and recovery (let alone subjecting the humans who use our systems to our own decision bias, taking away autonomy).

The second concept is seams. Research on interruptibility by Iqbal and Horvitz found that people can absorb interruptions far better at natural breakpoints, after completing a subtask or at the end of a sentence, than mid‑flow 2 . The cost of interruption at a seam is measured in milliseconds. Mid‑flow it’s measured in minutes of recovery time. This maps directly to interface design. We can ask someone to pause after they’ve typed a message, but interrupting them while they’re typing destroys the thought or rushes them.

Just‑in‑time intervention research reinforces this 3 . The most effective behavior change prompts arrive at decision points. Not randomly, not constantly, but right when someone is poised to act. The FDM uses seams as the architecture for friction: we only intervene where the mind can actually use the information.

What friction does Link to heading

Friction is a wayfinding tool. Dose it well and people remember what matters, avoid expensive mistakes, and trust the surface because it tells the truth about the curve ahead.

Two human facts set the boundaries. First, bad moments weigh more than good ones. Baumeister calls this negativity bias 4 . A denied transaction, a rejected appeal, a deleted post: these imprint deeper than smooth approvals. This isn’t a design flaw in human psychology. It’s an evolutionary feature. Our ancestors who learned more from negative outcomes survived longer. For product builders, this means friction at negative outcomes must be especially well-designed. Explain the criterion clearly, show the path forward, maintain respectful tone.

Second, naming what happened and what comes next reduces distress and helps people act. UCLA neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman calls this “affect labeling.” The simple act of putting feelings or situations into words activates prefrontal regions and dampens amygdala response 5 . When your payment fails, “Your payment didn’t go through” is far better than a generic error code. When you add “Your card wasn’t charged. Update your payment method to complete this order,” you’ve added orientation: what happened, what’s next, no blame. This isn’t just friendlier. It’s measurably more effective at getting people unstuck.

Beyond individual interactions, friction can shape habits over time by scaffolding new behaviors and then fading as mastery grows. It can protect communities and systems by throttling floods and routing low‑confidence cases to safer paths. And it can govern fairly by exposing criteria and offering real recourse.

The trick is knowing when it serves the person, when it serves the commons, and when it’s just sludge.

Designing helpful resistance, eliminating sludge and dark patterns Link to heading

Not all friction is desirable difficulty. Some of it comes from poor design. Some of it is deliberately designed to exploit. Let’s distinguish between them.

Helpful resistance has four qualities. It’s brief (measured in seconds or a single step, not multi‑screen odysseys). It’s legible (you can see why it’s happening and what it’s protecting). It’s proportionate (the resistance matches the stakes, confirming a $5 charge versus a $5,000 one). And escape stays visible (the exit or reversal path stays in view).

Think of Self‑Determination Theory’s three needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness 6 . Helpful resistance supports all three. Autonomy means you see clear choices and exits. Competence means you’re building a small skill or running a check you can actually use, not theater. Relatedness means the tone is respectful, the system explains itself, and there’s visible recourse.

Sludge is friction from poor design, not malice. Asking for shipping and mailing address separately without allowing copy between fields. Including unnecessary form fields (Why does buying socks require your phone number? It doesn’t). CSS and animations that slow down and confuse instead of clarify. Unclear error messages that don’t tell you what went wrong or how to fix it. Forms that don’t save progress. Fields marked “required” that aren’t actually required.

The tell: it could be fixed with basic usability testing, but nobody did that testing or nobody acted on the results. Often caused by technical debt, tight deadlines, overworked designers, weak QA, or teams that stopped looking at their own product with fresh eyes. Not intentional harm, just neglect.

Dark patterns are intentional exploitation. Deliberately confusing unsubscribe flows with multiple “are you sure?” screens designed to wear you down. Pre‑checked boxes for newsletter signups buried in terms of service. Confirm shaming (“No thanks, I don’t want to save money”). Making cancellation require a phone call while signup is one‑click. Hiding the “skip” button or making it invisible against the background. Fake countdown timers creating false urgency. Bait‑and‑switch pricing where the final cost balloons at checkout.

These exploit cognitive biases (loss aversion, status quo bias, authority) or simply deceive. The goal is to extract value from confused, tired, or rushed users who would choose differently if they had clear information and a moment to think.

The friction litmus tests:

- For sludge: Would this friction disappear if the team just looked at what they built and ran a usability test? If yes, it’s sludge. Fix with better QA, user testing, and the 12‑scenario probe mentioned later.

- For dark patterns: Does this friction exist because we’re trying to extract value from confused users? Does it disappear if we stop optimizing for “the platform wins when users are tired”? If yes, it’s a dark pattern. Fix with public commitments, ethics review, and governance that has teeth.

- For helpful resistance: Does this friction help the user make a better decision given the actual stakes? When Amazon introduced “returnable until January 30th” badges on holiday purchases, that was helpful resistance. It let buyers know exactly how reversible the decision was, changing the stakes and therefore the appropriate pace. When banks made overdraft opt‑out deliberately cumbersome, that was a dark pattern.

FDM prevents sludge through process (testing, accessibility audits, measuring regret signals). It prevents dark patterns through ethics (declaring commitments publicly, tying to governance frameworks like NIST AI RMF). And it creates helpful resistance by design, matching pace to stakes at natural seams.

The three dimensions in practice Link to heading

Let’s unpack each dial (Uncertainty, Novelty, Reversibility) with examples that show how they combine.

Uncertainty: what the system knows (and doesn’t) Link to heading

Modern AI systems can quantify their own uncertainty through techniques like conformal prediction 10 and Bayesian model uncertainty 11 . This isn’t theoretical. It’s the difference between “We matched your payment to Amelia Chen at 456 Oak Street (98% confidence)” and “We found several similar names; please confirm the recipient.”

Low uncertainty: “Your usual delivery address: 123 Main St, Apt 4B” gets no friction, just proceed. Medium uncertainty: “Similar to your saved addresses. Confirm: 123 Main St or 123 Main Street?” requires inline clarification, one tap. High uncertainty: “We found 3 Amelia Chens. Select the recipient” forces disambiguation with enough context to choose correctly.

Watch for uncertainty clusters. If the system consistently has low confidence on a particular demographic group (say, names with non‑Western characters or addresses in certain regions), that’s not a prompt to add friction universally. It’s a signal to fix the model or the training data. Adding friction to compensate for biased uncertainty compounds the trust erosion users experience.

Novelty: what the person knows Link to heading

This is where context length meets learning theory. First‑time actions deserve different treatment than the thousandth repetition. But “first‑time” is nuanced. First time in this category: never bought furniture online before, even though you buy books weekly. First time at this scale: first purchase over $1,000, first post to 10K+ followers. First time with these stakes: first non‑refundable purchase, first action that affects others.

Challenge‑hindrance theory helps here 9 . LePine’s research distinguishes between challenge stressors (difficult but growth‑oriented, like learning a new skill) and hindrance stressors (obstacles that block goals without adding value, like unclear instructions). When someone’s new to a flow, small challenges that build orientation are energizing. “First time posting a poll? Here’s a 15‑second preview.” Hindrance (making them hunt for basic features or decode jargon) just drains motivation.

Example flow: someone’s posting their first X thread. First thread ever? Show a minimal explainer (“Threads let you connect multiple posts. Add each post below.”) plus preview pane. Friction serves orientation. Third thread? Fade the explainer, keep the preview pane. Twentieth thread? No explainer, optional preview. Mastery has arrived. Get out of the way.

This scaffolding‑to‑fading arc appears throughout learning science. It’s how you teach someone to ride a bike (training wheels, then hand on the seat, then solo) and it’s how interfaces should teach complex actions.

Reversibility: what the action costs Link to heading

This is where the pace change becomes most visible. Fitts’s Law tells us that time to reach a target depends on size and distance 8 . Hick’s Law tells us that decision time grows with the number of options 7 . But both assume you want instant execution. Sometimes you don’t.

Easy to undo (message unsend, 10‑second window): minimal friction with countdown visible, one‑tap undo. The brief window creates a pocket for “wait, did I mean to send that?” without making you paranoid.

Conditionally reversible (purchase with 24‑hour cancellation): medium friction. Show the reversal window clearly (“Cancel free until 3pm tomorrow”), brief explainer if stakes are high, one‑tap access to the cancellation flow.

Hard or impossible to undo (custom manufacturing, non‑refundable booking, public post that gets amplified): serious friction. Short interstitial, plain‑English rationale (“Made to your specs; can’t be resold”), visible path to appeal or partial reversal. The goal isn’t to block action. It’s to ensure the person has genuinely chosen it.

Example: you’re about to buy a custom‑engraved watch for $800. The system shows “Custom orders ship in 3 weeks and can’t be returned” (what’s at stake), preview of your engraving (last chance to catch errors), and “Change your mind? Cancel within 24 hours for full refund” (the escape hatch that exists). This isn’t sludge because it’s brief, it directly addresses the non‑reversibility, and it gives you an out. Someone buying their fourth custom watch might see a lighter version, but for a first‑time buyer, this context is worth its weight.

Calibrating the dials together Link to heading

The dials don’t act alone. They combine to set the friction level. Low uncertainty plus familiar plus easy to undo means hint at most, no delay. Think reordering coffee beans from your usual roaster. Medium uncertainty plus unfamiliar plus conditional undo means inline note, optional checklist. First time renting a car in a foreign country gets clear explanations of insurance options. Low confidence plus first‑time plus hard to undo means short interstitial, brief hold, clear reversal path. Joining a waitlist that commits you to a $3,000 deposit if called needs that kind of pause. High confidence plus familiar plus permanent still gets brief confirmation out of respect for the stakes. Deleting your account after years of use deserves a moment.

What you’re reading for is felt alignment. When someone encounters friction, do they think “This makes sense given what I’m doing” or “Why is the system blocking me?” The former is FDM working. The latter is sludge or miscalibration.

Where friction lives (not just UI) Link to heading

Sometimes the respectful move is to slow the system, not the person. Friction has four addresses.

Computational friction. Route low‑confidence cases through a safer path. If fraud detection is at 65% confidence, don’t block the transaction and definitely don’t ask the user to prove they’re legitimate. Instead, trigger a second model pass, broaden the search, or route to manual review. The user experiences this as a slight delay with a progress indicator: “Verifying… this may take a moment.” That’s friction in the system’s decision path, not punishment for the person.

Data friction. When the world is under‑labeled (medical images in rare conditions, or content moderation for emerging slang), don’t make users do unpaid labor to fix your training set. Ask for the one label that reduces uncertainty or enables their recourse (“Which of these three options is closest?”), or fall back without busywork. If you need more labels, compensate for annotation or build better active learning pipelines.

Ethical friction. When decisions affect rights or high‑risk groups (credit, hiring, content visibility, healthcare), expose criteria, show alternatives, and write to a user‑visible ledger. This is Tyler’s procedural justice 12 as a surface, not a slogan. Did the person have input? Can they appeal? Can they see what criteria mattered? Is the tone civil, especially at negative outcomes?

Research consistently shows that people accept adverse outcomes better when the process feels fair, even if they disagree with the result. An apartment rental rejection that says “Your application was denied” generates far more distrust than “Income‑to‑rent ratio below building policy (3:1 required; yours 2.5:1). Want help calculating including a co‑signer?” The second version shows the rule, treats the person as capable of understanding it, and offers a concrete next step.

Interface friction. Adjust pace, tone, and visibility at the seam. Use inline notes and previews. Save hard blocks for actions that are truly hard to undo. Microsoft’s Human–AI Interaction Guidelines echo this structure 25 : set expectations early, support corrections easily, make failure modes legible, respect timing. These aren’t nice‑to‑haves. They’re the design equivalent of procedural justice.

Three textures: how friction feels Link to heading

We don’t always experience “uncertainty” or “reversibility” as clinical dials. We feel textures. Three are worth naming because they teach teams how friction lands on a person.

Engagement is attention with the task. The pleasant hum of challenge that sharpens focus without overwhelming. Csikszentmihalyi called this “flow,” the state where skill and challenge are balanced, feedback is clear, and the task absorbs you 17 . It shows up when something is new but safe to explore. You’re building your first database query in a no‑code tool. The interface offers a sandbox mode: “Try this query on sample data first. You can’t break anything here.” That’s engagement friction. It’s inviting you to explore without fear, which paradoxically makes you move faster once you understand the terrain.

What to measure: off‑topic errors, backspacing rate, task abandonment at early steps. When engagement friction works, confusion drops and people stop second‑guessing their way through flows. What it’s not: flow isn’t “make everything a game.” Forced gamification (points for actions that don’t need them, streaks that create anxiety) crosses into manipulation.

Reflection is the pause before the cliff. The tone turns candid, the signals behind a decision briefly surface, and the ask is concrete. It shows up when reversibility drops or uncertainty spikes. You’re about to post something that can’t be edited, send money that can’t be retrieved, submit an application that takes weeks to process. Instagram tested a feature where it detects potentially offensive language in comments and asks “Are you sure you want to post this?” before it goes live. Early data showed users revised or deleted the comment in a significant number of cases. That’s reflection friction. Not blocking speech, but creating a seam where people can reconsider.

What to measure: not just conversion. Watch 24‑hour reversals (cancellations, edits, deletes), regret signals (“I wish I hadn’t” replies, support contacts tagged with buyer’s remorse), and post‑outcome fairness ratings. Break this down by demographic and risk category to catch disparate impact. What it’s not: reflection isn’t a lecture. If your “pause” is a 500‑word terms‑of‑service popup or a guilt‑trip message, you’ve crossed into sludge or manipulation.

Resilience is work you opt into because the effort is the value or because the risk genuinely demands it. Practice loops (Duolingo’s “hard mode”), safety‑critical steps (confirming a wire transfer with two‑factor auth), or precommitments you set for yourself (“Don’t let me post after 11pm”). Gollwitzer’s implementation intentions show that when people precommit to “if X situation, then Y action,” they’re far more likely to follow through 20 . An app that lets you set “If I try to order food past midnight, make me confirm I really want it” is resilience friction. The user chose this guardrail because they know their future self benefits.

Another example: two‑factor authentication when logging into a hospital records system. The stakes (medical privacy, HIPAA compliance, patient safety) justify the extra step. But notice: good 2FA systems remember trusted devices and use risk‑based step‑ups, so you’re not entering codes every single time.

What to measure: completion rates where difficulty was raised, adherence to precommitments, false alarm rates for security step‑ups. If you’ve increased difficulty and adherence drops, you’ve miscalibrated. Either the person didn’t actually want this much friction, or you’ve made it hindrance instead of challenge. What it’s not: grit theater. If the only thing you’ve increased is performative effort (like requiring people to watch a 30‑second unskippable ad as “punishment” for a free service), that’s sludge dressed up as character‑building.

Attractors, not funnels Link to heading

Traditional conversion thinking imagines a single pipeline: Visitor → Prospect → Lead → Customer. Optimize each step, minimize friction, maximize throughput.

But people don’t actually move through a linear funnel. They settle into attractors, stable behavioral states that a system makes easier to enter than to exit. Impulsive share (see headline, instant post) versus deliberative share (read article, think about framing, post with context). Blind buy (one‑click, no reflection) versus considered buy (compare options, check reversibility, purchase). Reactive scroll (algorithmic feed pulls you deeper) versus intentional browse (you pick what to see).

Each attractor has its own basin, a region of the behavioral landscape where small nudges don’t change much. But crossing a threshold tips you into a different stable state.

This comes from dynamical systems theory, but you don’t need equations to use the insight. Place tiny seams on transitions between attractors (when someone moves from Explore to Decide to Commit to Appeal to Recover), and you can shift trajectories without heavy‑handed control.

Most social platforms optimize for the impulsive attractor. See something, react emotionally, share immediately. The basin is deep and easy to enter. Everything about the interface (the share button’s size, position, color, the absence of preview or fact‑check) pulls you in.

To make the deliberative attractor more accessible: put a seam at “share.” Detect if the person hasn’t opened the link. Show “Read first?” with a short preview (Twitter’s test 22 ). After sharing, if engagement is low or corrections are high, surface that signal gently: “This article has been updated since you shared it. View changes?” And make the better path easier over time. For people who consistently use previews, move the preview to be default‑visible, not a gate.

You’re not blocking impulsive sharing. You’re making deliberative sharing less effortful for people who want it, which gradually reshapes the attractor landscape.

Two detailed scenarios Link to heading

Let’s walk through two domains with concrete FDM applications.

E‑commerce: matching pace to purchase Link to heading

Routine reorder. Tenth bag of coffee beans from your usual roaster. Uncertainty is low (same vendor, same product, same card). Novelty is none. Reversibility is high (can cancel or return easily). Friction should be minimal. One‑click, brief confirmation, done. Maybe a “Cancel within 2 hours” note, but that’s it.

First‑time high‑ticket custom order. A $1,200 made‑to‑spec desk. Uncertainty is medium (new vendor for you, but vendor has strong reputation). Novelty is high (first furniture, first custom order). Reversibility is low (custom build, no returns). This deserves a measured lane. The interface shows: preview with your specs highlighted; “Custom orders ship in 4 weeks and cannot be returned or resold” (plain rationale); “Change your mind? Cancel within 24 hours for full refund” (the one escape hatch); one‑tap path to customer service if you have questions. This isn’t blocking purchase. It’s ensuring you’ve chosen this specific purchase with eyes open.

When fraud signals trigger (unusual shipping address, card from different country): Don’t punish the user. Route through backend verification (computational friction). Show a progress indicator: “Verifying order details… this usually takes 30 seconds.” If you must ask the user for something, ask for one confirmatory piece of info: “Confirm the last 4 digits of your card” or “Is this shipping address correct?”

Denial scenario. Transaction declined. Meet the procedural justice test 12 . Transparency: “Payment declined: card issuer flagged unusual activity.” Voice: “This wasn’t us; your bank blocked it. Call [number] or try a different card.” Respect: no blame, clear next steps, ETA if you provide one (“Usually resolved in 15 minutes”). Appeal: one‑tap to retry or to reach support.

Social platforms: disclosure and ranking Link to heading

Post visibility changes. Reach drops, content is age‑gated. Be transparent: “This post has limited visibility: mentions of [topic] are age‑gated per community guidelines.” Give voice: “Disagree? Appeal here. Response within 48 hours.” Stay respectful: neutral tone, no accusatory language. Show the top 2‑3 signals that mattered, not a data dump: “Flagged for: explicit language (2 instances), contested health claim (1 instance).”

Ranking lens disclosure. How does the feed decide what you see? Most platforms show a single algorithmic feed with no explanation. FDM suggests: disclose the active lens and offer one alternate. “Your feed: optimized for engagement. Try: chronological | close friends | topic‑focused.” Don’t bury this in settings. Surface it contextually: after a long session, after a report or hide, when someone seems frustrated.

This is Nissenbaum’s contextual integrity 13 . People consent to information flows when they understand the context. If the algorithm changes and suddenly your art posts aren’t reaching your followers, that’s a context violation. Disclosing “We’re testing a ‘recent interactions’ lens; your reach may change” repairs the violation.

Read‑before‑share. Fire only when the person hasn’t opened the link and it’s a news article or report (not a meme or personal blog). Show “Read first?” plus a 3‑line preview. Track open rate after prompt, regret signals (deletes within 1 hour), quality of discourse in replies. The friction is tiny (one extra tap, 5 seconds of reading). But the outcomes shift measurably: more informed sharing, less correction‑chasing in replies, higher trust from audience.

Measuring beyond speed Link to heading

If you only watch conversion rate and time‑to‑complete, speed will beat judgment every time. Add these four counters.

Reversals within 24 hours. Count cancellations, edits, or deletes on consequential actions within the first day. If these fall while conversion holds or improves, you’re gaining traction, not drag. If they rise, you’re pushing people through flows they’re not ready for. Target: less than 5% reversal rate on high‑stakes actions for experienced users, less than 15% for first‑timers (who are still calibrating).

Regret signals. Remorse deletes (posts removed within 1 hour, purchases canceled with “I didn’t mean to” notes). “I wish I hadn’t” replies or support tags. Post‑purchase support contacts tagged with buyer’s remorse. Target: downward trend over time as onboarding and friction improve. Spikes indicate either poor communication or misaligned incentives.

Procedural justice pulse. After hard outcomes (denials, removals, account actions), survey a sample. Did I see the criteria used? Could I explain my situation or appeal? Was the tone civil? Break this down by user segment. If one demographic consistently rates fairness lower, investigate disparate treatment or disparate impact. Target: above 70% positive on all three dimensions. Below 50% is a flashing red light.

Step‑up quality (for risk‑based gating). Where you use progressive friction (additional auth, fraud checks, content review), track true positives (how often did the step‑up catch actual bad behavior?) and false positives (how often did it block legitimate users?). Break this down by demographic. Are false positives clustered on certain groups? As your models improve, step‑ups should become rarer and more accurate, not more frequent. If your 2FA triggers are rising year‑over‑year, you have a model problem, not a security success. Target: false positive rate below 2% for risk‑based step‑ups. Above 5% means you’re adding friction faster than you’re adding signal.

Watch bandwidth harm (do constrained users pay the tax?) and insist on model‑aware gating (as calibration improves, step‑ups should fall, not creep). Measure friction encounter rate by device type, connection speed, and (where legally and ethically permissible) by demographic proxy. Then act. Optimize for the long tail. Compress assets for slow connections, simplify language for cognitive load, offer voice or visual alternatives to text‑heavy steps.

Tie all of this to the Microsoft Human–AI guidelines 25 and the NIST AI Risk Management Framework 26 so these numbers live inside governance, not as a dashboard island. When friction metrics degrade, they should trigger the same review process as bias metrics or security incidents.

Building this without drowning in process Link to heading

Theory is neat. Practice is messy. Here’s a pragmatic path.

Pick your rooms. Identify the 3‑5 places where consequences bunch up: high‑ticket checkout, refund or appeal denials, content sharing or amplification, ranking or visibility changes, account actions (suspension, deletion). Don’t try to FDM everything at once. Start where regret and harm are most visible.

Set thresholds for each room. For each room, decide what levels of uncertainty, novelty, and reversibility trigger a seam. Example for high‑ticket checkout: If fraud score is below 70%, route to additional verification. First purchase in this category? Show explainer plus reversal path. Non‑refundable? Require preview plus explicit confirmation of terms. Write these thresholds down. One sentence per dial per room.

Place friction at the lowest effective layer. Before adding UI friction, ask: can this be solved computationally (better model, second pass) or with data (clearer labeling, better defaults)? If you must add interface friction, place it at the seam closest to the decision: after typing, before sending; after adding to cart, before payment; after clicking “post,” before it goes public.

Expose a Decision Ledger. For consequential events, log which lens or rule triggered, what signals contributed (top 3), what overrides or exceptions applied, timestamp and user‑facing explanation given. Make a thin version of this visible to users on request. When someone appeals, they should be able to see “Your post was flagged for: [X, Y]. You appealed on [date]. Status: under review.” This is both an accountability mechanism and a design forcing function. If you can’t explain a decision in two sentences, your system is too complex or your criteria are too vague.

Run a 12‑scenario probe. Before shipping changes that touch risk, ranking, or high‑stakes flows: Write 12 scenarios covering best case (high confidence, experienced user, reversible action), worst case (low confidence, first‑timer, irreversible action), and edge cases (demographic variation, adversarial input, system failure). Walk each scenario through your FDM thresholds. What friction fires? Is it proportionate? Compare fairness and adherence metrics before and after. This takes 1‑2 hours. If it takes all afternoon, your system is underspecified.

Ship with a flag and a checkpoint. Launch new friction behind a feature flag. Set a two‑week checkpoint to review: conversion and time‑to‑complete (did it drop catastrophically?), reversals and regret signals (did they improve?), procedural justice pulse (do people feel respected?), step‑up quality (are you catching real problems or just annoying people?). If metrics improve, expand rollout. If they degrade, iterate or roll back.

One more rhythm that helps: the one‑hour loop. Scope one flow with measurable regret (15 min). Mark the seams (10 min). Write the reversal path (10 min). Decide what to log and show (15 min). Ship and checkpoint (10 min). If this loop takes all afternoon, the flow is either too vague or the stakes are genuinely high enough that you should invest more time.

Character, not theater Link to heading

The mechanics are the easy part. The promise is harder. When reversibility is low, explain before commit. When ranking changes, disclose the lens and one alternate. When outcomes are hard, meet the procedural justice test.

Keep a short list of these declared commitments and keep them in public view. Pin them in your docs, reference them in release notes, link to them in support articles.

Why? Because characters are kept by kept promises, not slogans. “We value transparency” is cheap. “Here’s exactly when and why we slow you down, and here’s how to appeal” is expensive. That expense is the point. It’s a costly signal that you mean it.

Speed is easy to sell. It converts well in A/B tests, it impresses stakeholders, and it makes demos feel magical. But speed isn’t trust. Trust is built when the system tells you the truth about the cliff before you walk off it. Trust is built when the system gives you a way out, even after you’ve committed. Trust is built when the system explains itself, especially when the news is bad.

FDM is a framework, but the ethos underneath is simpler: design surfaces that tell the truth about stakes. Make the easy things easy. Make the serious things feel serious, not because you’re lecturing or gatekeeping, but because you’re giving people the information and the pace they need to choose well.

That’s the promise of two tempos. Fast for routine. Serious when it’s serious. And always, always, the path back visible.

Sources

- Desirable difficulty. Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Psychology and the Real World. 1

- Interruptibility & seams. Iqbal, S. T., & Horvitz, E. (2007). CHI. 2

- Just‑in‑time interventions. Nahum‑Shani, I., et al. (2017). Behavioral Medicine. 3

- Negativity bias. Baumeister, R. F., et al. (2001). Review of General Psychology. 4

- Affect labeling. Lieberman, M. D., et al. (2007). Psychological Science. 5

- Self‑determination theory. Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). American Psychologist. 6

- Hick’s law. Hick, W. E. (1952). Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 7

- Fitts’s law. Fitts, P. M. (1954). Journal of Experimental Psychology. DOI:10.1037/h0055392 8

- Challenge vs. hindrance. LePine, J. A., et al. (2005). Journal of Applied Psychology. 9

- Conformal prediction (primer). Angelopoulos, A. N., & Bates, S. (2023). arXiv:2107.07511. 10

- Model uncertainty. Kendall, A., & Gal, Y. (2017). arXiv:1703.04977. 11

- Procedural justice. Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why People Obey the Law. Princeton. 12

- Contextual integrity. Nissenbaum, H. (2004). Washington Law Review. 13

- Counterfactual recourse. Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., & Russell, C. (2017). Harvard J. Law & Tech. 14

- Actionable recourse. Ustun, B., Spangher, A., & Liu, Y. (2019). FAT*. 15

- Habits & context. Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). Psychological Review. 16

- Flow. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow. 17

- Pace layers. Brand, S. (1999). Long Now Foundation. 18

- KLM/GOMS. Card, Moran, & Newell (1983). The Psychology of Human–Computer Interaction. 19

- Implementation intentions. Gollwitzer, P. (1999). American Psychologist. 20

- Present bias. Laibson, D. (1997). American Economic Review. 21

- Read‑before‑share. The Verge (2020) summary of Twitter tests. 22

- Risk‑based step‑ups. NIST SP 800‑63B (rev.). 23

- Accessible authentication. W3C WCAG 2.2 (SC 3.3.8). 24

- Human–AI guidelines. Amershi, S., et al. (2019). CHI. 25

- NIST AI RMF. (2023). 26